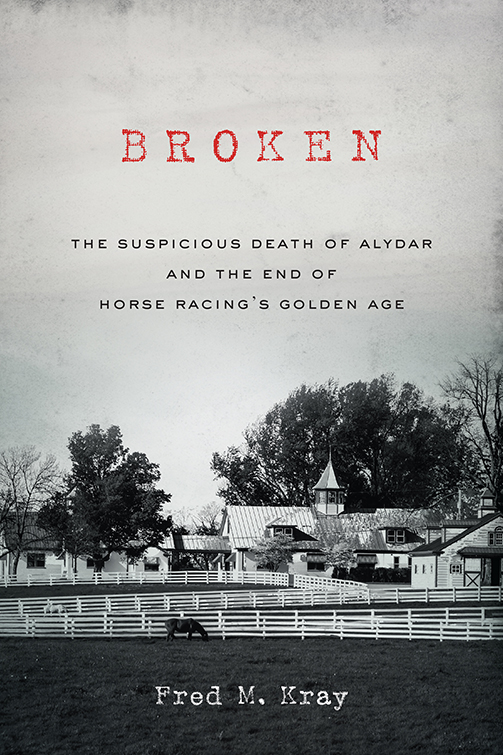

About the Author

In the Beginning…

My love for animals began early in life when my parents decided to get a Great Dane. Her name was Babe and she is my earliest childhood memory. We lived on a small island in New Jersey and everyone knew her. A gentle giant, she treated me as if I were her own. She watched over me, guarding my baby carriage and the story is told that she prevented me from walking out into a busy street by picking me up by my diaper and carrying me to safety. As I grew up, she was always by my side, my best friend, confidant, and protector. Every night she would come into my room to check on me, putting her head down, smelling me and looking at me with those large expressive eyes. My parents were from the “silent generation” where children were seen and not heard. There was not a lot of affection in our house. Babe gave me all her love and I needed it. I was always small for my age, and for a large part of my childhood, she towered over me. We were inseparable during the ten years I spent with her. Even as I grew, I was proud to be her friend. She was the foundation of my life growing up.

One day, a boy was beating me up in our front yard. Babe came running, growling, teeth showing and advancing. The boy ran off, and I hugged her desperately. I thought she would live forever. Then one day I woke up and she was gone. I still remember the date. September 6, 1962. I was ten years old. My parents thought it best to shield me from whatever medical problems led to her death and her death itself. The stiff upper lip was their way. But I didn’t get to say goodbye, and tell her what she meant to me. I never got over it. I was closer to her than any of my human family. Babe will forever be a large part of me, and she taught me that animals have beautiful, innocent souls and deserve our protection and stewardship.

High school was a rude awakening. Coming from a small island to a large high school, I had the early realization that I was a little fish in a big pond. I had to create my own circle of friends. The Beatles were dominating the airwaves, and everyone wanted to be in a band. I got a guitar, learned to play and joined several. I eventually became a bass player, because, well, it was the only instrument the band needed.

I went to college in Pennsylvania in the early 1970s. It was a time of no responsibilities and for trying new identities. Heavily influenced by Marvin Gaye, I started wearing a knitted cap. The only advice my father gave me during those years was to get a haircut before I came home. I knew from my own sensitivity and that I would never survive going to Vietnam. I wondered what my father would say if I went to Canada. He had served in the Navy after World War II and I presumed he would be disappointed. But it never came up. Although I drew a low draft number, I was lucky enough to get a student deferment in the last year it was available. But college campuses were in turmoil over protests against the Vietnam war and then there were the killings at Kent State. My generation was clamoring for change and turning against the middle-class lives that enabled their parents to pay their tuition. It seemed hypocritical to me at the time. Looking back now, I wonder what the legacy of the baby boomers will be: activism, social change and equality or creating an era of corrosive self-indulgence and materialism?

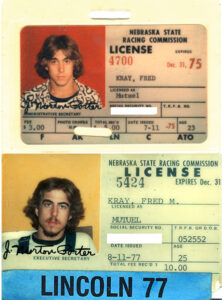

I graduated from college and did not want to sell IBM copy machines, a job the IBM representative with a crew cut assured me I would be perfect for if I just got a haircut. And I had already gotten one for the initial interview! Stalling, I went to law school in Lincoln, Nebraska without ever visiting the campus. It was a rash, impulsive decision, the kind you make when you’re 20 years old. I was a mediocre student, and worked at the racetrack in the summer which is where I developed my love for horses. I never tired of watching them make their stretch run. The powerful strides and exhalations of breath in sync with the thunder of hoofs as they raced to the finish line. A symphony of power and physicality. The stables were filled with the smell of fresh hay and manure. Each stall held a beautiful horse, noble in its own way.

My license for my first year, shows a clean-cut young man with a shirt that features horse stirrups, totally coincidental. But I would go through a rebellion of sorts, trying to look older and tougher than I really was. My license from 1977 has a mugshot vibe, the look I was going for at the time.

Adding to my anti-establishment image, I bought a motorcycle to ride, which was great until winter came, with temperatures routinely below zero and sometimes as low as -30. I also picked up a job in the winter pumping gas at a Holiday gas station, “Home of the Famous Stamp Bargains.” These were the days when there was no self-service. It was so cold you could hardly open the gas tank lid, and forget checking the oil. I had a red Holiday gas station jacket, which I wore to class, smelling of gasoline. The serious students wearing jackets and ties and interning at local law firms probably thought I should be thrown out of school. But I wanted to be James Dean.

After freezing in Nebraska for three years, I decided to go to Miami to practice law. My youthful appearance caused me problems from the very beginning. In my first case, the judge thought I looked so young that I was a teenage defendant waiting for his attorney. “I’m the lawyer,” I insisted. When my client arrived, he looked at me and said dubiously, “You’re my lawyer?” I won my first case with a little talent and a lot of pity.

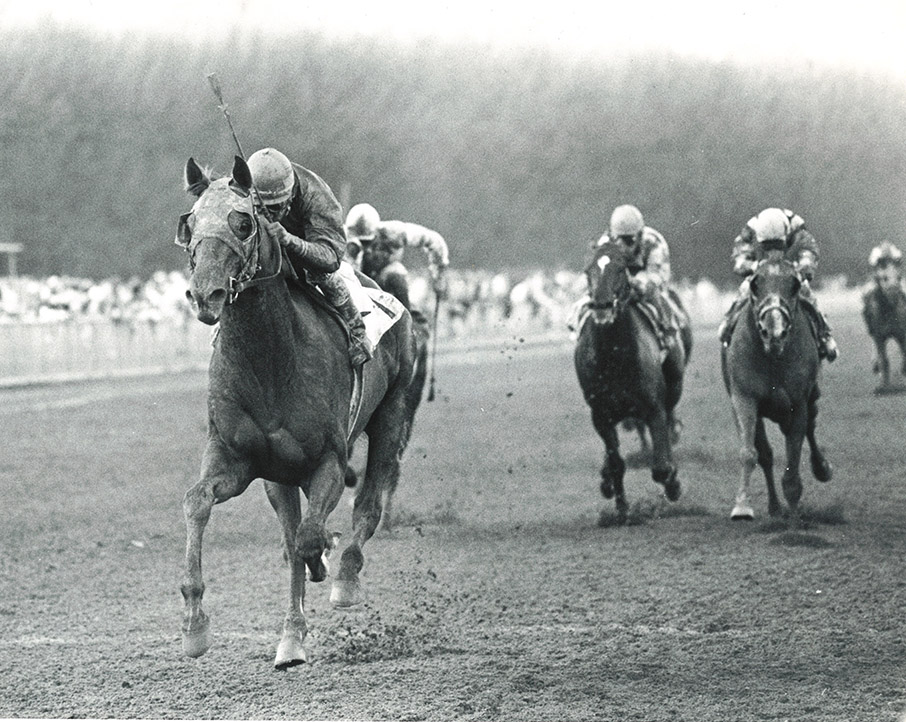

I was brought back to horse racing when I went to the Flamingo Stakes at Hialeah Race Course in March of 1978. There I saw the big burly horse from Calumet named Alydar, and fell in love. Watching his stretch run where he pulled powerfully away by four and half lengths was thrilling.

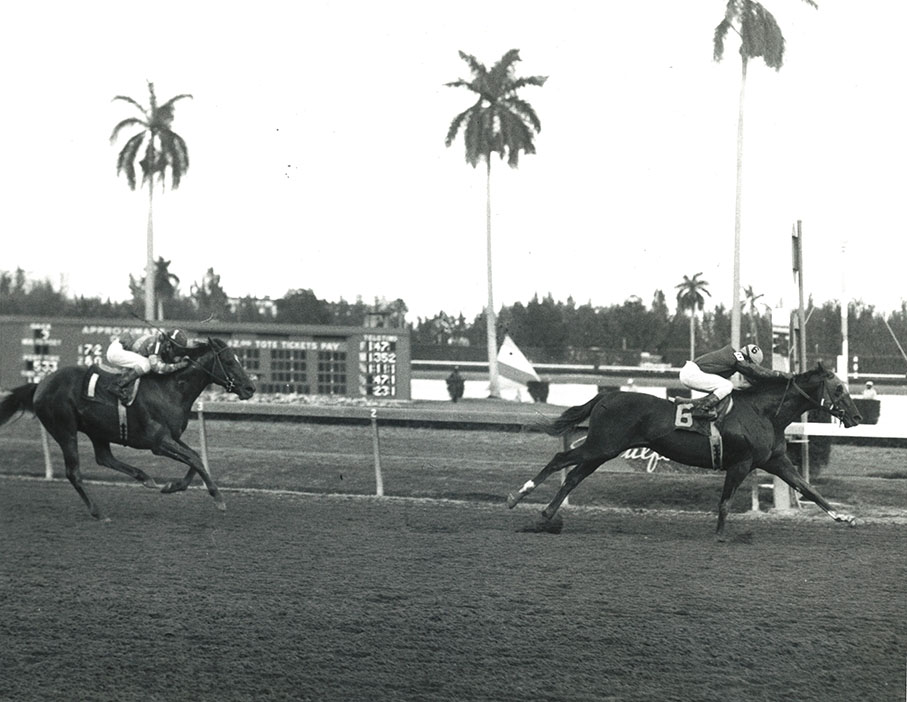

I followed Alydar to the Florida Derby at Gulfstream Park. I was seeing an old friend. In the end, Alydar pulled away by two lengths at the finish. I would never tire seeing Alydar in his trademark stretch run. He strided effortlessly and passed Believe It with a burst of speed. Sentimentality and nostalgia are weaved into my memory of those races that defy explanation.

That was the last I saw of Alydar in person, although I followed his races in the Triple Crown and Travers. I got lost in the world of judges, juries and trials. When Alydar died on November 15, 1990, I was so overwhelmed by work I didn’t even notice.

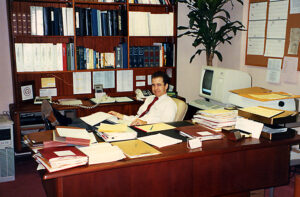

My world as a civil trial lawyer was serious. People were paying me to represent them. I became a part of the establishment that I had mocked in law school: blue Brooks Brothers suit, Florsheim shoes, white shirt and red and blue striped power tie. But I was good at it. I had so much work I had to close my office to new cases for a year. I became board certified, and tried bigger and bigger cases. I opened my own firm. But following me was one big problem. I hated it. The worry, the anxiety, and the fear drove me relentlessly. Every. Single. Minute. Somewhere in my 20th year I had what could only be called a nervous breakdown. I abruptly quit my job and immediately spiraled into a deep depression. With nothing to do, divorced, and questioning my identity, suicidal thoughts began creeping in.

Around this time, I received a ticket and court date fining me for not having one of my dogs licensed. But Redford had died months before his license was up for renewal.

“Court” turned out to be a glorified auditorium. People were milling around waiting for their case to be called. The judge sat at a small fold out card table and the defendant sat across from him in a fold out chair. The county representative sat next to the judge to his left, at a desk, looking at a computer monitor.

My case was called. The county representative was an imperious man who enjoyed wielding what little power he had. I had a dog and had not renewed his license in a timely way, and therefore a fine was due, he declared. The judge turned to me and said, “What do you have to say to that?”

I turned to the county representative and asked, “Does a dead dog need a license?”

“That depends,” he said, evasively.

“Let’s say we have a dead dog right here on the floor. Right now. Does he have to have a license?”

He looked at the judge for relief, but the judge said, apologetically, “Answer it.”

He paused, frowned, and finally said, “No.”

I reached into the plastic bag I had and took out my dog’s ashes. “These are the ashes of my dog, Redford.” I put them on the table. “Redford died well before the date the license was due and the cremains corroborate that.”

The judge looked at the county representative, unsuccessfully stifled a laugh, and said, “He’s got you there.” He paused a beat and then declared, “Case dismissed.” The audience burst into applause.

The county representative was not used to being challenged or being laughed at by the judge. The clapping audience only added to his humiliation. “We’re going to appeal,” he said angrily. He grabbed Redford’s box of ashes from the table and stormed off to the copy room.

After he was gone, I leaned over to the judge and said softly, “There’s nothing to appeal. They have no evidence to contradict my testimony. Why would the county waste money to do that?”

The judge looked at me earnestly and said in low voice, “They’re not going to appeal. He’s just mad because he lost.”

Later, I thought about what the judge had said. What happened to the other people who were in “court” today? It was the rare dog owner that could afford to hire a lawyer, and it was even more rare that a lawyer would know how to handle the case.

A weak sliver of light disrupted the blackness of my mind. I wanted to do this. I would give animals a voice in the courtroom. I found the courage to go to therapy and see a psychiatrist. I was diagnosed with OCD and given a medication that calmed the constant firing of the electrical charges surging through my brain. The depression lifted.

My animal law career began. I fought to keep undeserving dogs off death row, some used as pawns in neighborhood disputes, others wrongfully convicted because their owners didn’t know how to contest the charges. I recovered a stolen Great Dane with a five-man SWAT team and a battering ram. I sued to stop puppy mills. I freed friendly pet pit bulls from euthanasia based on administrative decisions that a dog just looked like a pit bull and it should be banished from its home. I was Counsel for the Plaintiff in Nelson v. Town of New Llano, LO, 2:14-cv-0083 US Dist. Ct. Western District of Louisiana, litigation of a breed ban resulting in repeal and co-counsel for plaintiff in Criscuolo v. Grant County, WA – U.S. Dist. Ct. Eastern Dist. Wash. 2012 No. CV-10-470-LRS, litigation of breed discriminatory legislation resulting in repeal.

Nothing touched my heart more than seeing a dog wrongfully held by animal control reunited with its owner.

Brandie, improperly convicted in the wrong jurisdiction being

hugged after release from death row. Copyright Lon Lipsky.

I lectured around the country on Animal Law and testified against breed discrimination in Boston and Indiana.

I was also an Adjunct Professor of Animal Law at Barry University College of Law and co-authored Defense of Dangerous Dog Classifications, 128 Am. Jur. Proof of Facts 3rd 291 (2012). In 2016, the American Bar Association presented me with the Animal Lawyer of The Year award. In 2019 I received the SEEDS Award, for my Contributions to the Field of Animal Law. I was humbled by the recognition, and was totally surprised.

I moved to Gainesville, and continued my animal law practice in Ocala, Florida. It has over 400 horse farms, and is where Affirmed, Alydar’s greatest rival was born. I took a horse farm tour in Ocala. The tour director, making small talk, asked me what started my interest in horse racing, and the conversation turned to my work at the racetrack in Nebraska and then to Alydar, who I had seen win The Flamingo Stakes and The Florida Derby. She said, “You know, the lady driving the other bus was at Calumet when Alydar died.”

The tour bus operator pulled me away from our group and we walked to meet Ms. Calumet. We interrupted her tour, and the three of us walked off to the side.

“This man is interested in Alydar,” the tour bus operator said. Ms. Calumet frowned. She was short, thin, and wiry, like someone who still worked with horses.

“You were on the farm when Alydar was injured?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. She looked away from me and her tone of voice made it clear that she didn’t want to talk about it and wished the tour bus operator hadn’t mentioned her connection to Calumet.

“Do you know what happened that night?”

“Everybody who worked on that farm knows what happened that night,” she said. “That barn was protected. Security guards would run out if you got near. Security was taken off. That never happens.”

“Do you think that J.T. Lundy did it?”

“He didn’t physically do it. He aligned it. He was down here in Ocala with an ankle monitor.”

“I’d like to interview you.”

“No, I won’t.” Her answer was final, no argument.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because I value my life and my children’s life,” she said.

“What are you afraid of?”

“Good luck.” she said, not meaning a word of it. She scowled at me, turned abruptly on her heel, and walked off. We all pretended nothing had happened for the rest of the tour.

Even after reading everything on the internet, I couldn’t understand how Alydar’s accidental injury happened. Lloyd’s of London and Golden Eagle insured Alydar for a total amount of $36.5 million. $15 million went to owners of breeding rights, $20.5 million went to First City Bank (within thirty days), and $1 million was paid to Calumet.

Alydar’s groom, Alton Stone, had been tried and convicted of making false statements to a grand jury. J.T. Lundy, Calumet Farm’s president along with Gary Matthews, Calumet’s CFO, had been convicted of conspiracy, bank fraud and bribery, and making false statements to a bank.

That Ms. Calumet was still afraid was surprising. Wild Ride, a book published in 1994 documenting Calumet’s financial demise, had described Lundy’s relationship with the Mafia. Was that it? A scene from The Godfather, where a man wakes up in a sea of blood with a horsehead in his bed. crossed my mind.

Prosecutors had tried for years to indict someone for Alydar’s death. It was naïve to think I could do better than the FBI after three decades had passed. I thought of Alydar, in shock, steaming, and shivering alone in his stall at 10 P.M. on November 13, 1990, with a broken cannon bone. Then his chiseled muscular body stilled in death. His chestnut coat slicked in sweat and matted with woodchips. It was unspeakable.

I had to try.